Living Underwater, Part I: Why has the true inventor of the scuba device we use today gone unrecognized?

The invention of the scuba regulator valve enabling people to breath compressed air and swim freely underwater is widely misattributed exclusively to Jacques-Yves Cousteau.

The invention of the first practical scuba regulator—developed as the result of the feverish enthusiasm of amateur inventors and entrepreneurs—is often misattributed solely to Jacques-Yves Cousteau. Though he was the codeveloper, together with engineer Emile Gagnan, of a single-stage twin breathing hose regulator valve, it is not the design that has become the mainstay of present-day scuba. Ted Eldred, a quiet Australian, independently developed a quite different two-stage single-hose regulator but did not patent his invention—at the time he couldn’t afford the cost. Cousteau's American manufacturer, US Divers, noticed the popularity of his design and pressured Eldred into surrendering the design rights. Divers preferred Eldred’s design over Cousteau's technically inferior twin-hose model. Sadly, embittered by his experience, Eldred fell into obscurity and only received recognition for his major contribution to modern scuba late in his life.

Scuba1, emerged in the late stages of World War II and the early 1950s, revolutionizing undersea exploration. But its roots go deeper—into wartime Europe, and particularly to the coast of Vichy-administered France along the Riviera. There, under Nazi occupation, spearfishing became a wildly popular pastime, offering both escape and subsistence. As in other parts of the world where spearfishing flourished, diving enthusiasts and inventors began experimenting with ways to stay underwater longer without having to surface for air. This period of innovation, driven by necessity and curiosity, laid the groundwork for the modern scuba system. Before its advent, divers—somewhat akin to the barnstorming pilots of the 1920s—relied on bulky oxygen rebreathers or surface-supplied air delivered via hoses. Oxygen rebreathers were in use by the military and some commercial divers but were maintenance-intensive and expensive. Additionally, their safe use required expertise, making them an unpopular and particularly inaccessible solution for recreational divers.

Want to see where the story goes next? Part II, traces how while saturation diving has become operational practice for commercial diving—while the vision of establishing permanent undersea habitats was ultimately left behind.

The breakthrough came with the application of a diaphragmatic demand regulator valve and the ability to carry compressed air cylinders, enabling divers to breathe underwater at the surrounding pressure and to be able to move with the ease of a true creature of the sea. The breakthrough opened up the world beneath the waves to millions of recreational divers by enabling them to carry compressed air cylinders on their backs and breathe through a regulator valve adjusted for underwater pressure.

The diaphragm-based demand valve was the key innovation that truly liberated the diver from the burdensome and risky equipment prior. The device was originally designed by Émile Gagnan for regulating the carburetors of cars using cooking gas in wartime France in the 1940s. Cousteau’s connection came through his father-in-law, an executive at L’Air Liquide for whom Gagnan worked. The formation of a subsidiary company, La Spirotechnique, led to the production of the first "Mistral" twin-hose diving regulator. The second hose was cumbersome but necessary to counterbalance the pressure difference caused by placing the regulator behind the diver's head and having air intake through the mouthpiece.

It’s commonplace for the Cousteau-Gagnan demand valve, together with the legendary advocate for all things underwater, to be credited almost exclusively with the development of modern scuba with this invention. However, history tells a different and, in most respects, a more interesting and compelling story.

Two decades ahead of Cousteau, another Frenchman, Yves Le Prieur, made groundbreaking contributions to underwater exploration in the 1920s-30s with his invention of the first practical autonomous diving apparatus. His 1926 compressed air single-flow regulator system—featuring a hand-controlled valve that delivered continuous airflow from a high-pressure tank—allowed divers unprecedented mobility underwater without surface connections. This innovation laid critical groundwork for modern scuba technology, but history has often overlooked Le Prieur's achievements, giving more recognition to Jacques-Yves Cousteau. Despite their friendship and Cousteau's awareness of Le Prieur's work, Cousteau frequently claimed exclusive credit for inventing self-contained underwater breathing apparatus when he and Émile Gagnan developed their demand regulator in 1943. Nonetheless. Le Prieur's earlier pioneering work represents a vital but underacknowledged foundation for the evolution of contemporary scuba diving technology.2

The Coast of Coral and the Man from Down Under

The arrival of the Cousteau-Gagnan Aqua-Lung in Australia is a story spiced with intrigue and industrial espionage. In 1947, a French company brought the first Aqua Lung regulators to the French Pacific territories. An enterprising diver spotted this revolutionary device and bought one. He later connected with the Australian Navy's Chief Diving Instructor in Sydney, and the two men carefully disassembled the unit, created detailed drawings of its inner workings, and proceeded to have copies made. Divers in the Australian navy began to make use of these “knock-off” copies.

While Air Liquide had officially appointed Siebe Gorman—a well-established manufacturer of traditional diving equipment—as its distributor for Australia and New Zealand, the real breakthrough came through unofficial channels.

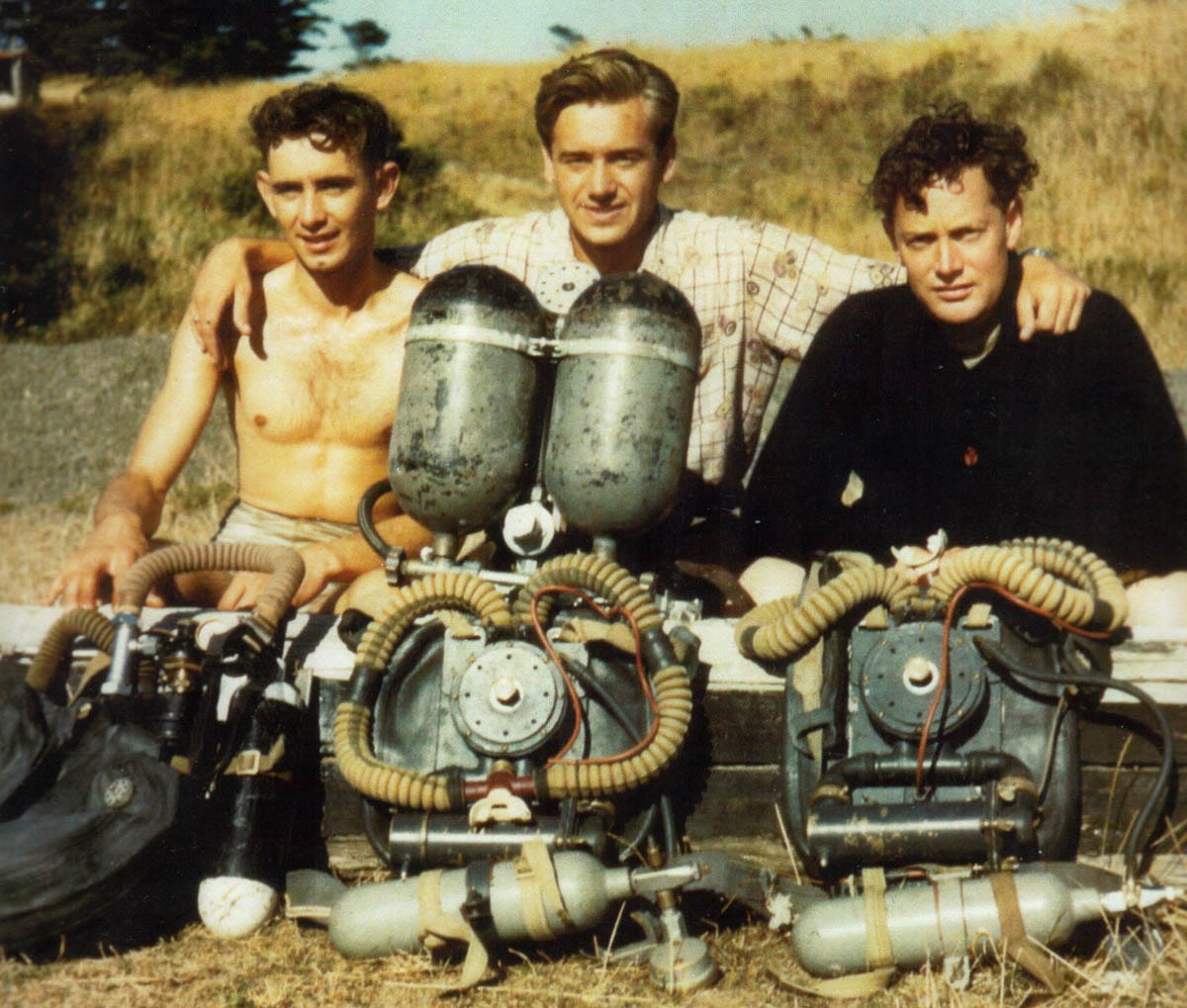

In 1949, a Frenchman, Michel Callaud, arrived in Australia with intimate knowledge of the Cousteau-Gagnan design, though without an actual unit. He collaborated with colleagues Ted Baker and George McGann, and together they constructed three regulators from scratch. This design was then acquired by another entrepreneur, and a further twelve units were manufactured in his factory, adding his modification—mounting the regulator on the diver's chest for easier breathing. These Australian-made units achieved their moment of fame when they were used in the filming of "King of the Coral Sea" in 1953, which contains a number of underwater photography sequences that compare the traditional technology with that of scuba-equipped divers. 3

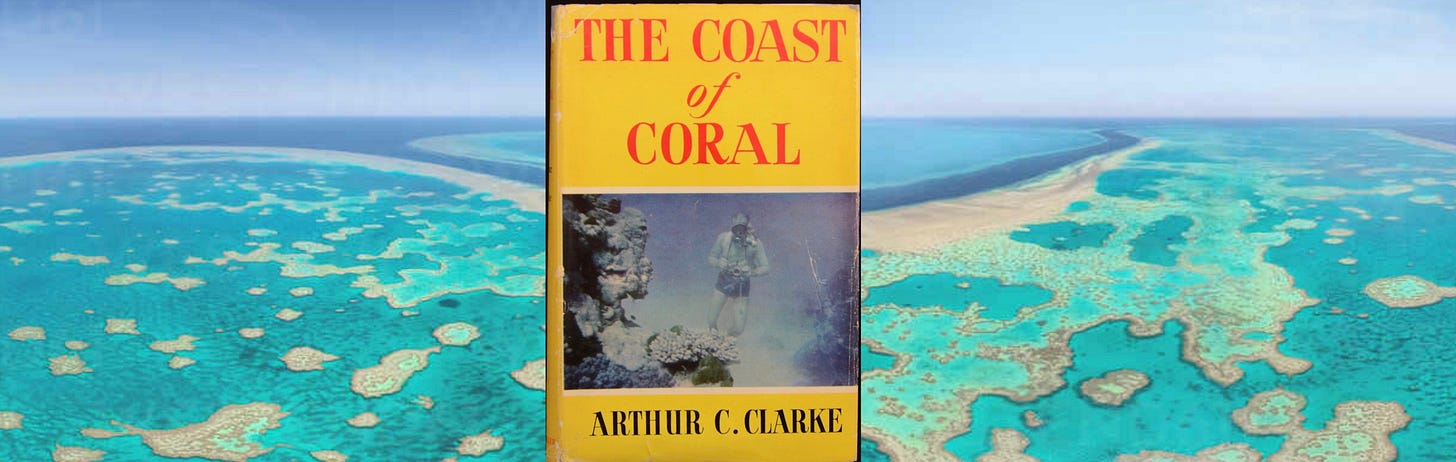

Around the same time, the technological innovation that was to truly revolutionize scuba came from Melbourne, where Ted Eldred was quietly developing something far more significant than another knock-off of the Cousteau-Gagnan design, about which he had heard but never seen. While others were replicating and modifying the flawed twin-hosed single valve system, Eldred engineered an entirely new approach. His Porpoise CA-1 single-hose regulator, unveiled in 1952, eliminated the awkward second hose and solved the fundamental pressure differential problems that had plagued the French design and were caused by placing a single-stage demand valve behind the diver’s head. This arrangement required a second hose to allow the air exhaled by the diver to pass directly over the valve’s pressure compensating diaphragm to balance the differential air pressure. Without this modification, the Cousteau-Gagan valve was prone to delivering disproportionate amounts of air depending on the diver’s orientation in the water. Without having seen the Cousteau-Gagnon design and having previously developed chest-mounted oxygen rebreathers, Eldred decided to incorporate a small diaphragmatic demand valve into the diver’s mouthpiece and add a first-stage pressure reduction through a high-pressure hose attached between the mouthpiece and the first-stage reduction valve on the compressed air tank strapped to the diver's back. This innovation would ultimately become the template for modern scuba regulators worldwide, and as the popularity of his regulator exploded in Australia, it soon drew the attention of Cousteau and the licensees of his design. The invention came about in an extraordinary way. The science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke resided in Sri Lanka and was an underwater enthusiast. 4 He learned of Ted Eldred’s diving school and the regulator that he had developed, visited, and trained with, taking it with him for the diving he undertook for his book about the Australian Great Barrier Reef and the Coral Coast. Already a celebrity figure for his science fiction writing, Clarke’s book, like his science fiction, was a giant bestseller, and its cover had a photograph of Clarke underwater—not with the twin-hosed Cousteau-Gagnan “Mistral,” but rather an unusual single-hosed design homegrown down under.

Discovering that Eldred’s design was not protected by patent, US Divers, Cousteau's American licensee, employed coercive tactics, forcing Eldred out of the market and taking control of his design.5 Only towards the end of Eldred’s life was his contribution to the technical innovation that made modern scuba possible recognized. Eldred’s story has been retold as the result of a number of oral histories and documented accounts of the fate that befell the young Australian inventor for not having patented his design. By the time his work was finally appreciated, Eldred had long since abandoned inventing gear but diving as well, disillusioned by his experience of corporate exploitation. 6 In the US around the same time (1949-50), another diving enthusiast, E.R. Cross, had also developed a two-stage single hose regulator similar to the Eldred design. Neither Eldred nor Cross was aware of the other’s work. Historians of this topic note that many scuba regulators and oxygen rebreathers produced in the immediate post-war period were “knock-offs” of other designs. Equally well recorded was the coercive business practices at play by the larger manufacturers of diving equipment to keep the burgeoning market for themselves.7 Ironically, Cross did not register his design for a patent for the same reason as Eldred - lack of financial resources.

Pioneering underwater cinematographers like Hans and Lotte Hass provided the world with its first mesmerizing glimpse beneath the waves by the late 1960s. Their groundbreaking work set the stage for Jacques-Yves and Simone Cousteau, whose Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau captivated tens of millions around the globe. Like the Hasses before him, Cousteau helped transform undersea exploration from a niche scientific pursuit into a global popular fascination. Yet, as compelling as Cousteau’s documentaries were, they also cemented a widespread misconception: that he alone invented the scuba apparatus that allowed humans to breathe underwater freely.

In truth, Cousteau cannot be solely credited with inventing the two-stage demand regulator, the essential piece of equipment for modern scuba diving. While Cousteau and engineer Émile Gagnan co-developed the Aqua-Lung in 1943, Australia’s Ted Eldred independently advanced regulator technology, and his design significantly influenced the development of modern regulator valves used in scuba diving today, unlike the earlier Cousteau-Gagnan design. Eldred’s Porpoise regulator made critical improvements that history has too often overlooked. The development of scuba was a collective achievement, refined over decades by inventors, engineers, and, ironically, by the very community of recreational divers that Cousteau’s cinematography helped inspire.

The late 1960s and 1970s ushered in the first major refinements to scuba technology since the invention of the regulator. Divers seeking greater control underwater drove the evolution of Buoyancy Compensator Devices (BCDs), moving from simple manually-inflated life jackets to integrated jacket-style BCDs that allowed fine-tuned buoyancy adjustments during a dive. Innovations such as aluminum tanks, balanced first-stage regulators, and more comfortable wetsuits made diving safer and more accessible to a growing global audience.

Take a deep breath

By the late 1970s, the arrival of dive computers like the Orca Edge began to replace complex decompression tables, making deeper and longer dives safer and simpler. The 1980s and 1990s saw recreational divers pushing the limits of traditional diving, leading to the emergence of technical diving. This new frontier went beyond standard recreational limits, employing mixed gases like Trimix, using rebreathers to recycle breathing gas, and exploring depths and environments once thought too extreme. Pioneers like Sheck Exley and Dr. Bill Stone laid down safety protocols and expanded the technology needed for these bold endeavors, while organizations like Technical Diving International (TDI) formalized training standards that continue today.

The gear used by technical divers—backplate-and-wing buoyancy systems, multi-gas computers, sidemount configurations—filtered back into recreational diving, just as earlier innovations had. Technical divers mapped deep wrecks, explored flooded cave systems, and expanded human understanding of fragile marine ecosystems, demonstrating that recreational diving was no mere pastime but a vital enabler of scientific, commercial, and conservation achievements.

Meanwhile, the recreational diving industry exploded. Certification agencies like PADI, SSI, and NAUI standardized diver education and issued millions of certifications worldwide.8 Diving destinations such as the Great Barrier Reef, the Maldives Islands, Cozumel, and the Red Sea became magnets for adventure seekers. Innovations continued into the 2000s and 2010s: dive computers integrated real-time environmental data, LED lighting and high-resolution underwater cameras flourished, and rebreather technologies became increasingly accessible to civilians.

At the same time, the importance of safety grew. Buddy systems, pre-dive safety checks, and emergency procedures became embedded into dive culture. Equipment standards regulated by EN, ISO, and CE certifications ensured reliability, while advances in dive medicine and the expansion of hyperbaric treatment centers improved survival and recovery from diving accidents.

Ironically, while governments funneled billions into space exploration during the same decades, it was recreational divers—not navies or scientific expeditions—who truly opened up the oceans to human experience. Recreational divers raised public awareness about coral reefs, marine ecosystems, and the dangers threatening them. The demand for better gear, more training, and safer practices drove an entire industry forward, one that now embraces sustainability, accessibility, and citizen science as it prepares for future challenges and opportunities.

Despite sophisticated innovations, the fundamentals of scuba diving have remained unchanged for over half a century: a compressed air tank, a regulator, fins, and a mask still define the experience. Free divers and snorkelers continue ancient traditions, but scuba diving remains humanity’s primary window into the marine world. Ted Eldred’s neglected role in scuba’s technological genesis serves as a broader reminder: innovation is often communal and evolutionary, not the triumph of a single name.

If you enjoyed this you may also like to read Ariadne’s report on the United Nations Conference on the Oceans:

"Scuba" entered dictionaries in the late 1950s after recreational diving gained worldwide popularity. Coined in the 1940s by Christian J. Lambertsen for a military rebreather system, the acronym (Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus) has since been lexicalized. It is now referenced as a lowercase noun referring to both equipment and activity, exemplifying how specialized terminology can be absorbed into common language, often with users unaware of its technical origins.

Campedelli, Andrea, Yves Le Prieur and the Discovery of Underwater Space, Blue Time History, 2022

Selina Tan and Dennis Yew, Born in Asia: Tracing the Paths of Scuba Inventions Posted on August 9, 2019

Arthur C. Clarke (1917–2008) was a British science and science fiction writer who rose to international prominence in the 1950s and remained widely recognized through the Moon landing, when he appeared as a commentator alongside Walter Cronkite during the Apollo 11 broadcast. Best known for co-writing the screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) with director Stanley Kubrick, Clarke also authored the novel of the same name. Long before satellite technology became reality, he famously predicted the concept of geostationary communication satellites in a 1945 article for Wireless World, envisioning global television and data networks. A former RAF radar specialist during World War II, Clarke earned a science degree from King’s College London in 1948 and began writing speculative fiction and popular science shortly thereafter. Among his early novels were Prelude to Space and The Sands of Mars (both 1951), but he also brought scientific wonder to general audiences through nonfiction. His 1956 book The Coast of Coral introduced readers to the Great Barrier Reef’s underwater world and helped popularize the newly emerging technology of scuba diving.

Maynard, Jeff, Who Invented the Aqualung? Posted on December 9, 2022

Fibonacci, Scubaboard, Porpoise CA-1 Regulator , Jan 14, 2019

Dowsett, Kathy, About Ted Eldred, Designer of the “Porpoise”, The ScubaNews, March 28, 2024

Cousteau never acknowledged Ted Eldred as the inventor of the single-hose regulator. It’s also well documented that Eldred was subjected to unethical and coercive business practices from US Divers (licensed to produce the Cousteau-Gagan regulator design) that enabled them to produce Eldred’s design without his being acknowledged or fairly compensated. See Jeff Maynard

It is fascinating that Eldred came up with his design with very little knowledge of the Gagnan device. Similarly, Dr. Hans Hass, a less well-known rival of Cousteau, is now recognized to have reached several milestones before the more celebrated Frenchman but was slighted by Cousteau’s unwillingness to acknowledge these. Hass published his first book of underwater photographs, “Diving to Adventure,” in 1939 and released his first underwater film, “Stalking Under Water,” a year later. Mr. Cousteau made his first film in 1942 and published his first book, “10 Fathoms Down,” in 1946. Hass was also the first to use self-contained oxygen delivery equipment for underwater exploration years before the Cousteau-Gagnan Aqualung.

Both received international acclaim for their documentary films: Dr. Hass won first prize at the Venice Film Festival for his first feature, “Under the Red Sea,” in 1951, and Cousteau won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1957 for “The Silent World,” co-directed by Louis Malle and based on his 1953 book of the same title. It’s generally accepted that Hass developed the first underwater cases for Roliflex and Hasselblad cameras significantly ahead of any underwater photographic equipment built by Cousteau. Together with his wife, Lotte Bayerl, Hass developed lighting techniques and other processes essential to underwater photography, also ahead of Cousteau.

Both Cousteau and Hass received Academy Awards. Lotte Bayerl was elected into the Women’s Divers Hall of Fame in 2000. Tim Ecott, the author of “Neutral Buoyancy” (2001), a history of underwater exploration, asked Hass if he resented Cousteau’s greater renown. “No, why should I be bitter? The sea is so big,” Hass responded, but then added sharply, “For Cousteau, there existed only Cousteau. He never acknowledged others or corrected the impression that he wasn’t the first in diving or in underwater photography.”

Baldinucci, Maurizio, History of the Single Hose Regulator, Blu Time History, 2022. It is now widely accepted that the single hose, two stage regulator valve was conceived of independently by three individuals two American and one Australian, of these neither Eldred nor E.R. Cross patented their designs. James Fleming, a talented American aeronautical engineer did come up with the same solution receiving a patent around 1958. By the early 1960’s Emile Gagnan now working in Canada for Cousteau’s company La Spirotechnique, had fully incorporated Eldred’s design into the US Divers product line. Ted Eldred was never credited or received any royalties from the use of his design.

Following WW II up until the mid-1960s, there was a burgeoning interest in scuba in the US, Australia, and Asia with clubs primarily organized for scuba diving, though lacking any national or international regulations or standards. Pioneering groups, particularly in the United States, set about establishing curricula, courses, and certifications for scuba diving instructors. The history is fascinating to read, as it recounts the dedication and commitment of numerous individuals. A good starting point is here. There are now millions of scuba divers being certified each year worldwide, and in some locations, tens or even hundreds of thousands of divers who regularly pursue recreational diving. The largest organization for scuba diving instruction in the world is PADI .